The cornea is the front cover of the eye. It acts like a window to allow the image to enter the eye and helps focus it on the retina in the back of the eye. Therefore, it is a very important structure of the eye that has to stay moist and clear at all time. Many things can go wrong with the cornea ranging from common dry eyes, scratched cornea, infections, and vision-threatening conditions such as corneal ulcer, keratoconus, and Fuchs’ dystrophy.

Keratitis is an inflammation of the cornea. Keratitis can occur due to abrasion, trauma, infection, or underlying diseases such as Sjogren’s syndrome and lupus. Keratitis can lead to blindness.

Dry eye syndrome (also known as dry eyes or keratoconjunctivitis sicca, KCS) is a very common condition that is caused by a disturbance of the tear film. This abnormality may result in disruption of the ocular surface, causing a variety of symptoms that interfere with quality of life.

A thin tear film coating the eye is made up of three layers: the innermost mucous layer, the middle watery layer, and the outermost oil layer. Any disturbance in the balance of the components will lead to dry eye syndrome.

Dry eye syndrome is a common disorder of the normal tear film that results from decreased tear production, excessive tear evaporation, and an abnormality in the production of mucus or oil normally found in the tear layer, or a combination of these.

Common symptoms are gritty/scratchy, or filmy feeling, burning or itching, redness of the eyes (conjunctivitis), blurred vision, foreign body sensation, and light sensitivity. The symptoms are worse towards the end of the day, in dry or windy climates, and in winter months.

During an eye examination, the eye doctor will most likely be able to diagnose dry eye syndrome just by hearing the patient’s complaints about his or her eyes. Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by seeing signs of dry eyes. As part of the eye examination, the following tests may be performed:

There is no cure for dry eye syndrome and some people have recurring episodes for the rest of their lives, but there are treatments to help control the symptoms. The exact treatment for dry eye syndrome depends on whether symptoms are caused by the decreased production of tears, tears that evaporate too quickly, or an underlying condition.

The underlying problem with long-term dry eye syndrome is inflammation in and around the eye. Therefore, one of the anti-inflammatory treatments mentioned below may also be recommended.

-Corticosteroid Eye Drops and Ointments

Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory medications that can be given as eye drops or ointments in severe cases of dry eye syndrome. They have side effects such as cataract formation and raising the pressure within the eye in about one in every five people. This group of treatments should only be used if you are being monitored by an eye doctor. Common steroids in these groups are prednisolone acetate 1%, Lotemax, Tobradex.

-Oral Tetracycline

Low doses of a medication called tetracycline can be used as an anti-inflammatory agent for a minimum of three to four months, sometimes much longer. The most common tetracycline used is doxycycline.

-Cyclosporine (Restasis) Eye Drops

Cyclosporine is a medication that suppresses the activity of your immune system and is commonly used in the treatment of dry eye syndrome. The commercially available form of prescription cyclosporine eye drop is called Restasis. It is used twice a day and requires up to 3 months to see improvement in dry eye symptoms.

-Autologous Serum Eye Drops

In very rare cases, where all other medications have not worked, autologous serum eye drops may be required. Special eye drops are made using components of your own blood. It is only available through a local compounding pharmacy. To make autologous serum eye drops, one unit of blood is taken under sterile conditions (as for regular blood donation). The blood cells are then removed and the remaining serum is put into eye drop bottles. Because of quality standards, this process can take several days before the treatment is finally available to use.

-Punctal Occlusion

Punctal occlusion involves using small soft plugs called punctal plugs to seal your tear ducts. This means your tears will not drain into the tear ducts and your eyes should remain moist. In more severe cases, the tear ducts are cauterized (sealed using heat). This permanently seals the drainage hole to increase the amount of tears on the surface. This can be performed in combination with lubrication treatment.

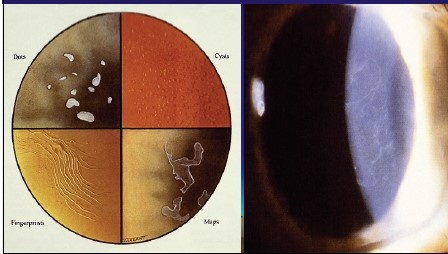

Map-Dot-Fingerprint Dystrophy (also known as Epithelial Basement Membrane Dystrophy or simply EBMD, and Cogan’s Dystrophy) is a disease that affects the top layer of cornea. It is commonly called Map-Dot-Fingerprint Dystrophy because of microscopic dot and fingerprint-like patterns that form within the layers of the cornea.

The cornea is comprised of five layers. EBMD affects the superficial corneal layer called the epithelium. The epithelial bottom, or basement layer of cells‚ becomes thickened and uneven. This weakens the bond between the cells and sometimes causes the epithelium to become loosened and slough off in areas. This problem is called corneal erosion.

Even though this disease is commonly known as a dystrophy (a term that describes genetic diseases), EBMD is not necessarily an inherited problem. It often affects both eyes and is typically diagnosed after the age of 30. Cogan’s usually becomes progressively worse with age.

Most patients with EBMD have no symptoms at all. The symptoms among patients may vary widely in severity and include:

The doctor examines the corneal layers with a slit lamp microscope. In some cases, corneal topography (surface curvature map) may be needed to evaluate and monitor astigmatism (shape irregularity) resulting from the disease.

The treatment for EBMD is dependent on the severity of the problem. The first step is to lubricate the cornea with artificial tears to keep the surface smooth and comfortable. Lubricating ointments are recommended at bedtime so the eyes are more comfortable in the morning. Salt solution drops or ointments such as sodium chloride (Muro 128) nightly for several months are often prescribed to reduce swelling and improve vision. Gas permeable contact lenses are occasionally fitted for patients with irregular astigmatism to create a smooth, even corneal surface and improve vision.

For patients with recurrent corneal erosion, soft, bandage contact lenses may be used to keep the eye comfortable and allow the cornea to heal. In some cases, laser treatment may beneficial. The surgeon removes the epithelium with an Excimer laser (same laser used in LASIK surgery) to create a rough but regular surface (similar to sanding plank before painting). The epithelium quickly regenerates (similar to applying new paint), usually within a matter of days, forming a better bond with the underlying cell layer.

Fuchs’(pronounced fÅ«ks not fyooks) endothelial dystrophy is a non-inflammatory, autosomal dominant, dystrophy involving the endothelial (innermost) layer of the cornea. With Fuchs’ dystrophy the cornea begins to swell causing glare, halo, and reduced visual acuity. The damage to the cornea in Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy can be so severe as to cause corneal blindness.

Eye examination shows cloudiness and swelling in the center of the cornea and roughness on the inner layer of the cornea. It appears like orange peel rather than the glossy apple skin. This makes it seem like looking through frosted glass.

General treatment is symptomatic. At this time there is no treatment to reverse or halt the progression of Fuchs dystrophy.

Medical treatment of Fuchs’ dystrophy begins once patients notice fluctuation in vision. Typically, it is worse upon awakening and improves towards the end of the day as the eyes dry from air exposure between blinks. Here are the medical treatment options:

As Fuchs’ dystrophy progresses its medical treatment may fail, at that point surgical management becomes necessary. For many years the only option for patients with visually significant Fuchs’ dystrophy was a full thickness corneal transplant or penetrating keratoplasty (PKP). A corneal transplant involves replacement of the full thickness of the cornea in order to replace the endothelial cells. The cornea is held in place with multiple sutures and some sutures may stay in place for several months to years. Over the past several years there has been a trend to try and treat endothelial dystrophies by transplanting only the posterior, or endothelial, portion (posterior lamella) of the cornea. Posterior lamellar surgery has been refined over the past several years and now is becoming the standard of care in treatment of early to moderate Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. The most popular surgical procedure is currently named Descemet’s Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSEK) or Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK). Please refer to Corneal Transplant and DSEK sections on this website for more details.

Keratoconus is a condition in which the clear front structure of the eye (the cornea) bulges outward like a cone. It is caused by the weakness in the structure of the cornea.

Tiny fibers of protein in the eye called collagen help hold the cornea in place and keep it from bulging. When these fibers become weak, they cannot hold the shape and the cornea becomes progressively more cone shaped.

Keratoconus appears to run in families. If you have it and have children, it’s a good idea to have their eyes checked for the condition starting at age 10. The condition happens more often in people with certain medical problems, including certain allergic conditions. It’s possible the condition could be related to chronic eye rubbing. Most often, though, there is no eye injury or disease that can explain why the eye starts to change.

Keratoconus usually starts in the teenage years. It can, though, begin in childhood or in people up to about age 30. It’s possible it can occur in people 40 and older, but that is less common.

The changes in the shape of the cornea can happen quickly or may occur over several years. The changes can stop at any time, or they can continue for decades. In most people who have keratoconus, both eyes are eventually affected, although not always to the same extent. It usually develops in one eye first and then later in the other eye.

The earliest signs of keratoconus are usually blurred vision and frequent changes in eye glass prescription, or vision that cannot be corrected with glasses. Symptoms of keratoconus generally begin in late teenage years or early twenties, but can start at any time.

Other symptoms include: